|

|

|

|

|

|

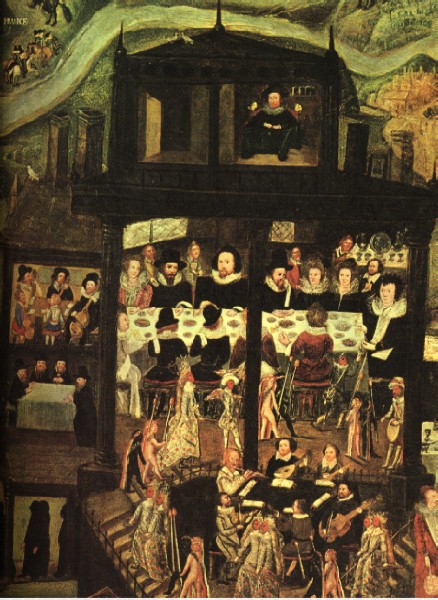

To this day people engage in banquets like people did in the Elizabethan Period. Though the menus have changed, the idea of social gathering with food is just about the same. People now can go to places such as "Old Country Buffet" (a popular "all you can eat buffet") and eat an extravagant amount of food that almost anyone could afford. Another important difference between modern day buffets and Elizabethan banquets is this: only the royalty and the wealthy in those days could afford to have such a feast because a peasant obviously could not afford roasted peacock or swan. Now all a person needs is $8.14 to stuff himself or herself silly. The menus of Elizabethan feasts usually consisted of such foods as these:

First Course

Second Course

Third Course

Dessert One famous ceremonial feast consisted of 50 crabs, 18 trout, 9 large and 9 small pike, 4 large salmon, 18 brill, 10 large turbot, 200 cod tripes, 50 pounds of whale, 200 smoked and 200 pickled herring and a numerous amount of food after that. Banquets of these times were so big that hosts employed servants for the oddest job tasks. One example would be the bread trencher; his job was to get fresh bread and replace it with the old bread that had gotten stale during the meal. People of this time did not use the utensils that we use now. They thought that using their hands to scoop out the food was much more efficient. Several table manner books came out at this time because it was most obvious that one did not want to eat after his or her neighbor scratched himself and then scooped food out with the same hand. During the Elizabethan Period people prepared a wide variety of foods that would be unheard of in restaurants today. English people were very visual about their food. They loved strange shapes and particularly enjoyed dishes of unusual colors. Unusual dishes included such treats as small birds in a pie, roast peacock, hedgehogs, or roast Swan. Even though they did not eat such dishes as swan and peacock, they were used as a centerpiece decoration among the royalty. An Elizabethan recipe for hedgehogs has been translated for people of the 20th century: Hedgehogs. Take Piggis mawys, & skalde hem well: take groundyn Porke, & knede it with Spicerye, with pouder Gyngere, & Salt & Sugre; do it on the mawe , but fille it nowe to fulle; then sewe hem with a fayre threde, & putte hem in a Spete as men don piggys; take blaunchid Almaundys, & kerf hem long , smal, & scharpe, & frye hem in grece & sugre; Take a litel prycke, & prykke the yrchouns, An putte in the holes the Almaundy, every hole half, & eche fro other; ley hem then to the fyre; when they ben rostid, dore hem sum whyth Whete Flowre, & mylke of Almaundys, sum grene, sum blake with Blode,& lat hem nowt brone to moche, & set forth.Serves 6-8

2 lb (4 cups) minced (ground) pork Modern Translation: Mix the pork, breadcrumbs, spices, seasonings and softened butter. Bind with the beaten egg yolks and form a ball. Place in a buttered pan. Cook, covered, for 1 hour, basting at intervals with the rest of the butter melted in the vegetable stock or water. Stick the slivered almonds, dyed with the vegetable colouring, all over the pudding, so that they look like the quills of a hedgehog or a sea urchin (recipe from Seven Centuries of English Cooking).

|

|

In eating breakfast, many people wanted a fine diet. Instead of eating normal bread, many ate manchets. Manchet was a round loaf which weighed about six pounds after it was cooked. It was browner than normal bread. When bread was eaten in the morning, butter was used to flavor it so that the bread was not so boring. Children often ate butter in Lent. However, adults who kept the fast strictly avoided butter during this time. Eggs were also eaten at breakfast. They were eaten "sunny side up" or beaten to make scrambled eggs. They were also mixed with bread crumbs to fry things such as fish. Another popular food for breakfast was pancakes, which were made from flour and egg batter. They were a treat for Sunday mornings. Elizabethans usually put jams such as grape, strawberry, and sometimes powdered sugar on them for a sweeter taste. Breakfast, the hardiest of all their meals, gave a healthy start to their day. In earlier times, water was the main beverage. However, as farmers became more important, other drinks came along also. Milk was known for building healthy bones and giving a refreshing taste after a dessert. Farmers got milk from cows and she-goats. Other sources of liquid were a part of stews and potages. Other beverages were created from a wine base. A famous hot wine recipe from this time is as follows:

1/2 put (275 ml) water Bring the water and wine to a boil in a sauce pan. Put in the almonds and add the ginger, honey, or sugar and salt. Stir in the saffron or food coloring, and leave off the heat to stand for 15-30 minutes. Bring back to a boil, and serve very hot, in small heat proof bowls. Another popular wine base drink was a caudle, a hot drink thickened with eggs and drunk at breakfast or at bedtime. There were many differences between the meals of the higher and lower classes. Dinner was the most important meal for any class and came usually from 10:00 a.m. till noon. Ploughmen were well-scrubbed and usually ate at bare tables. Country table manners were not the daintiest. In a well-to-do household, however, a greater ceremony was observed. There was a cloth placed upon the table. Next, a trencher, a napkin, and a spoon were set at every place. Elizabethans loved fine linens. An Elizabethan dinner usually consisted of several kinds of fish, half a dozen different kinds of game, venison, various salads, vegetables, sweet meats, and fruits. Rich men usually served food that suited them. Most had noted French chefs to prepare their meals. Many had a very moderate diet. Guests at a pleasant dinner table were offered oysters with brown bread, salt, pepper, and vinegar. A pepper box and a silver chafing dish were among the table accessories. The wine was kept cool and fresh in a copper tub full of water. Each time a guest handed back an empty glass or goblet it was rinsed in a wooden tub before being refilled. Guests were able to choose between roast beef, powder (salted) beef, veal and a leg of mutton with a "galandine sauce." There was often a turkey, boiled capon, a hen boiled with leeks, partridge, pheasants, larks, quails, snipes, and woodcock, in addition to the other foods. Salmon, sole, turbot, and whiting, with lobster, crayfish, and shrimps, were set before dinner guests. Young rabbits, leverets, and marrow on toast tempted those who did not care for the gross meats. Artichokes, turnips, green peas, cucumbers and olives were provided as vegetables. Attractive salads, including one of violet buds, were also served as vegetables. Finally, the host or hostess would usually offer guests quince pie, tart of almonds and various fruit tarts. They would also be offered several kinds of cheese and desserts, including strawberries and cream.

The midday meal in a good citizen's home consisted of certain coarser foods like sausage, cabbage (usually badly cooked) and porridge for the children. It was customary to spend two to three hours over this chief meal of the day. The nobility, gentleman, and merchant men commonly sat at the board till 2:00 or 3:00 in the afternoon. Country fare was given with fat capon or plenty of beef and mutton. They also recieved a cup of wine or a beer. They were also given a napkin to wipe their lips. In the holiday season, rich and poor alike indulged in leisure time and feasting. People in the middle and lower classes ate lots of potages and stews. They also had fish and vegetables at dinner. Behind the first cooked potages was the tradition of food processing. This consisted of soaking roots, leaves, seeds, nuts, and berries in cold water. They were soaked several hours in order to soften them, which made them easier to digest. Next, the pot boiler method was used for cooking meat in water to make it more tender. Potage was made primarily from cereals and large weed seeds, which were roughly ground into bits and pieces. Altogether there were many things to eat during this period. Overall the diet was much healthier than what many people eat now. During the holiday seasons everyone, including farmers and laborers, celebrated in holiday feasts. The two main parts of a normal diet in the Elizabethan England time were bread and meat. Bread was the most important component of their diets. The wealthy people ate manchet, a loaf made of wheat flour. In the country districts, a lot of rye and barley bread were eaten. Another important component of an average diet was meat. England had been noted for its meats and means of preparing them. The English had a way of making tainted meats edible. First, a person would remove the bones from the meat. Then, they would wrap it in an old, coarse cloth. After it was wrapped, they would bury it at least three feet underground. It was left underground from twelve to twenty hours. When the meat was dug up, they found it sweet enough to eat. They also used a lot of spices to add flavor to the unrefrigerated meat. Soaking the meat in vinegar and adding sauces also flavored the meat. One particular meat dish was Polonian Sawsedge, usually eaten from November to February, when fresh meat was scarce. The dish was made from the fore part of a one or two year old tame boar. It was a very heavily spiced dish. The recipe is as follows:

Platt's Recipe for Polonian Sawsedge "Take the fillers of a hog; chop them very small with a handful of red sage: season it hot with ginger and pepper, and then put it in a great sheep's gut; then let it lie three nights in brine; then boil it and hang it up in a chimney where fire is usually kept; and these sawsedges will last a whole yeere. They are good for sallades or to garnish boiled meats, or to make one rellish a cup of wine." In Elizabethan times, the word "herb" stood for all things that were green. This included things from grasses to trees. One popular vegetable of the time was turnips, which were usually either boiled or roasted. The poor, however, ate them raw. Artichokes were eaten raw with added salt and pepper. Aaparagus, which was known as "sperage" during this time, was boiled and eaten with salt, oil, and vinegar. The sweet potato, a popular dish, was roasted in ashes, sopped in wine, or topped with oil and vinegar. Sometimes, sweet potatoes were even boiled with prunes for flavor. Regular potatoes were also either boiled and roasted. The cooking techniques related to the kitchens of the landowners. There was invariably some kind of fresh meat to replace the preserved foods on which lesser households depended in winter and spring. Fresh or salted ingredients were used according to availability. Cooks used a great deal more than a pinch of pepper, ginger, cinnamon and saffron due to the starchy ingredients and creamy sauces. Many techniques and materials solved contemporary food preporation problems. Texture was important because of the limited number of eating tools used. Most people carried a general-purpose dagger-shaped knife and spoons. The dinner fork was an oddity until the 18th century. People tried inventing different eating tools but failed. A few eccentrics used a fork for dining, but most continued to eat with their fingers. Supposedly, it was Henry VIII who introduced the fork into England. In some places, such as the Navy, knives and forks were regarded as being prejudicial to discipline and manliness. The absence of the table fork would have had few repercussions on table manners, had it not been for the way in which the service of food was organized. Very high ranked men had their own dishes, plates, and drinking cups. No napkins were used at this time. Men had to remember to clean their hands before their meal and keep them clean during the meal. Other table manners were not to blow one's nose with the fingers and not scratch at any anatomical parts at the table. Poking at the meat or any dish was considered unpleasant and annoying to others. When dinner guest were finished with the meal, the bones were thrown on the floor, not on the plate. This was a custom in elevated households. Finally, to finish the meal right, a delicate burp was acceptable. Whether one was a member of the high or low class, manners were the same for everyday life. In conclusion, food and dining were a part of everyday life in Elizabethan time. They had many different dishes and styles of cooking. They also had distinct manners and traditions that went along with their meals.

|

|

Sometimes the meats were not fresh at all. Fish is a good example. When the people of the Elizabethan Age got fish, it was not always fresh, so they had to bring out the flavor by adding herbs and spices. The people of the Elizabethan Age ate eggs a lot. They used eggs in every possible way. With eggs they made omeletts, fritters, pancakes, and stuffings. They also used eggs as thickeners in sauces and stews. The people of the Elizabethan age ate different types of meat like beef, mutton, pork, veal, carp, pike, eels, and other fish. They also ate dried fruits, such as raisins, prunes, and dried apricots. Although salads were made from onions and herbs, vegetables were not very popular in the Elizabethan Age. People in this time period just didn't eat many vegetables. People of the Elizabethan Age baked and ate bread a lot. Bread was the staff of life. The darker breads were called cheat, cocket, or whole-grain. Sometimes the people of the Elizabethan Age used oats for breads. They drank different things like ale, cider, perry, beer, red wine, white wine, and metheglin. Breakfast in Elizabethan England consisted of bread, beer, wine, herring or sprats. It also consisted of boiled beef or mutton. For dinner the people of the Elizabethan Age ate different meats, salads, and fruits. For dessert or to top the dinner off, they ate something sweet like jellies, different cakes and pies, or pears with caraway. They made different types of recipes for the meals they ate for breakfast and dinner. The people of the Elizabethan Age even sometimes went on diets. When they dieted they ate black bread, milk, cheese, and eggs. The people of the Elizabethan Age ate many of the different types of food we eat today. We just have a greater variety of foods to choose from.

|

|

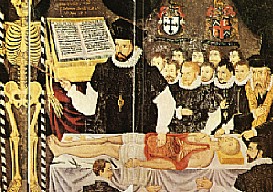

Beliefs. All in all, medicine remained mostly medieval in Elizabethan times. Many physicians based their philosophies on the teachings of Aristotle and Hippocrates. These beliefs were widely accepted during the Medieval period. However, the emphasis on magic and astrology diminished in Elizabethan times. Yet, some physicians still believed that if the planets were out of line, an individual would get sick, according to his or her own sign. The strongest and most widespread belief was that of the four humours and four elements. The humours are bodily fluids, and the seat of all these fluids was thought to be the liver. The four humours are blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Supposedly the level of humours in the body characterized the personality. If a person had more blood in his body, he was characterized as having a sanguine personality. These people were very passionate, amorous, joyful, and kind. With abundance of phlegm, the personality was characterized as being phlegmatic or cowardly, unresponsive, and lacking in intellectual ability. Yellow bile meant that the person had a choleric personality. These people were generally believed to be obstinate, vengeful, impatient, and easily angered. Black bile meant that the person was melancholy or excessively brooding, gluttonous, and satiric. There were also four elements that were thought to determine a person's personality and health. The four elements were air, water, earth, and fire. Air was the cold element, water the moist, earth the dry, and fire was the hot element. Belief in the humours took a long time to die out. Elizabethan physicians also believed that certain gemstones held medicinal powers. Garnets were believed to keep sorrow at bay. Topaz and jacinth were used to alleviate anger. Emeralds and sapphires were thought to ease the mind. The College of Physicians. The College of Physicians was founded in 1518, through the efforts of Thomas Linacre. The chairs of the board were professionals who were educated at universities such as Oxford, Cambridge, and Padua. To be issued a license, a doctor had to have a mandatory university education. The College earned its right to do dissections on human corpses in 1565. These bodies were usually the bodies of convicted and executed criminals. Cures. Cures were basically concoctions of several different herbs that were thought to be of medicinal value. These concoctions were usually home remedies or ones prescribed by "old wise women" and soothsayers. Those who could afford a doctor's care would fill their prescriptions at an apothecary. Different ingredients and herbs would be used for different parts of the body. For instance, head afflictions were treated with sweet-smelling herbs such as rose, lavender, sage, and bay. Heart problems were remedied by plants such as saffron, basil, and rosemary. Stomach aches and other related sicknesses were treated with wormwood, mint, and balm. Lung afflictions such as pneumonia and bronchitis were treated by liquorice and comfrey, which is still used in bronchitis medicine today. Renowned Physicians. The greatest physician of Elizabethan times was William Harvey (1578-1657). Harvey was educated at Caius College, Gonville, and Padua. Harvey first described the circulation of the blood. Although Harvey did not publish his findings until 1628, he spoke of his discovery in his lectures much earlier. Thomas Linacre (1460?-1524) founded the College of Physicians and later became the physician to Henry VII and Henry VIII. Linacre earned the title "restorer of learning" to England. This title was given mainly because he expressed a critical awareness that the writings of such authoritative figures as Galen should be translated and read accurately. Hierarchy of Medical Professions. Physicians were not the only ones who provided medical care. They were, however, the only ones who had to be licensed according to the College of Physicians' rules, regulations, and guidelines. To acquire a physician's education and skill, one had to come from a family with at least a little wealth. Physicians could charge high fees, as they enjoyed a high professional status. The poor would have to rely on home remedies or medicine administered by charitable churches. The College of Physicians kept its standards high, but those physicians who practiced in the country had lower guidelines than those of city doctors. Surgeons were considered to beinferior to physicians. They usually operated on a physician's instruction. The surgeons tended to have a bad reputation, mainly because they shared company with barbers.

Though surgeons were usually more knowledgeable than barbers, they all belong to a group called the Company of Barber Surgeons. Even though barbers belonged to the same Company as the surgeons, they were not allowed to practice much besides blood-letting and tooth-pulling. The last rung on the ladder that was the medical profession of Elizabethan times was the apothecary, or dispenser of drugs. The apothecaries came to be known as the physician's cook and were associated with grocers because they were essentially just that. Apothecaries also endured bad reputations at times. Some were not so ethical in their distribution of medicine. Often they would sell fraudulent prescriptions or miracle cures that a country bumpkin would pay hard-earned money for. In 1616, apothecaries received a Royal charter to practice independently without physicians checking up on them. Diseases. The main cause for disease in Elizabethan England was probably the lack of sanitation. The streets of cities, towns, and villages were unadulterated cesspools. There were open sewers in the streets, which were also used as community garbage cans. This kind of atmosphere was the perfect breeding ground for rats, lice, fleas, viruses, diseases, and germs, all of which were common problems. One of the biggest killers of Elizabethan times was the Plague, or "Black Death," a disease carried by rats who bred in the dregs of the sordid streets. Typhoid, a disease that was spread by improper sanitation, was also a problem. A second cause may have been the diet, or lack thereof, of many Elizabethan people. The rich frequently got gout; their diet primarily consisted of meat and not many fruits and vegetables. Many of the residents of rural Elizabethan England were probably malnourished and suffered diet-related ailments. Scurvy, a disease that results from the lack of vitamin C in the body, was common. Toothaches were also a common, more minor problem. These afflictions were cared for by the barbers. A tertiary cause for disease was the exploration of the world. The explorers brought more than just tales, spices, riches, and knowledge. They brought back with them diseases like smallpox and syphilis, diseases which could be passed from person to person by physical contact or drinking or eating after someone. In conclusion, Elizabethan medicine was not very advanced. Old beliefs overshadowed the knowledge of new discoveries about the human body. However, the medical profession advanced through the establishment of standards and a common board by which the public could benefit.

|

|

Leon: Where is but a humour of a worm? These lines from Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing give a brief glimpse into the world of Elizabethan medicine. The beliefs, practices, and medical problems of the sixteenth century were very different from those of today. One of the most common beliefs during this time concerned the humours. It was believed that four humours or fluids entered into the composition of a man: blood, phlegm, choler ( or yellow bile), and melancholy ( or black bile). According to this belief, the predominance of one humour over the others determined a person's temperament as sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric, or melancholy. Furthermore, they believed that too much of any of them caused disease, and that the cure lay in purging or avoiding the peccant humour, as by reducing the amount of blood by cupping or reducing the bile by means of drugs. Epidemic diseases became more common in the sixteenth century. Among them were typhus, smallpox, diphtheria and measles. Scurvy also increased in frequency. During this time leprosy became rare. In children there were epidemics of plague, measles, smallpox, scarlet fever, chicken pox, and diphtheria. Many children were abandoned, especially infants with syphilis (it was feared they would pass it on ). Dental disease sometimes caused death, and congenital and acquired blindness were also common for the children. In the sixteenth century syphilis continued to be common. The favored treatment was with mercury or guaiac. Gonorrhea became even more common. These two venereal diseases were directly responsible for the stopping of communal baths, which were the only convenient means of personal hygiene. Elizabethan medical treatments were quite varied. The first effective remedy for ague (malaria) was a plant derivative from Peru called cinchona. It cured quickly and acted specifically on only a certain kind of fever. The belief in fever as a general manifestation of unbalanced humours received a severe blow. It was then felt that each fever could be different diseases. For an earache, a common remedy was to put a roasted onion in the ear. To cure a stye, a person was supposed to rub his eye with the tail of a black tomcat. Captain Cook kept his sailors healthy from scurvy by giving them lemon juice, a source of much-needed vitamin C. For mental illness, Jean-Baptiste Denis extended the new technique of transfusing blood to the treatment of mental patients. When arterial blood of lambs was injected into the venous system, the patients seemed to recover. This method was stopped when a patient died. Large scale preventative measures for epidemic diseases did not come about until over a hundred years later. In 1764, Dr. Clarke inoculated against smallpox with the virus of the disease itself. The doctors discovered that if people had one slight attack of small pox, later they were immune to the disease. In 1776, people who contracted cowpox seemed to be protected from smallpox. The physicians of the Elizabethan period were men of good education. Their degrees were generally taken abroad and were then incorporated at Oxford or Cambridge. A very thorough examination had to be passed before licenses were granted for practicing in the metropolitan area. The college was less severe about licenses to practice in the country. Ambroise Pare, an army physician, discovered the effectiveness of hygiene on wound healing. One night after treating many gunshot wounds with boiling oil, he ran out of oil. Many soldiers' wounds were uncared for, so Pare simply cleaned and dressed their wounds and went to bed. The next day he awoke to see that the wounded treated with oil were feverish and in pain, while the ones cleaned and dressed were sleeping and doing well. As Pare's fame grew, his story was made common knowledge, and boiling oil was no longer used on the battlefield. Pare also reintroduced the ancient method of stopping hemorrhage by using ligatures. He influenced many practitioners to abandon the cauterizing irons. In 1616, physician William Harvey studied of the circulation of the blood and disproved the existing notion that the heart was merely a fountain of supply. For the first time he demonstrated the real action of the heart and the course that the blood took through the arteries. Other physicians had suggested this explanation, but Harvey was the first to demonstrate it. Jan Baptista Van Helmont believed that fever was not due to an excess or unbalanced humours but represented a reaction to an invading irritating agent. He declined to use bloodletting and purging and rejected their supposed value in restoring the humoral balance. He used chemical medicines and improved on the use of mercury. In conclusion, Elizabethan medicine was very different from our present day practices and beliefs. Furthermore, the medical problems of the sixteenth century were very different from those of our own time.

|

|

The bubonic plague originated in Central Asia, where it killed 25 million people before it made its way into Constantinople in 1347. From there it spread to Mediterranean ports such as Naples and Venice. Trade ships from these Mediterranean ports spread plague to the inhabitants of southern France and Italy. It had spread to Paris by June of 1348, and London was in the grips of plague several months later. By 1350, all of Europe had been hit by plague. From this time to the mid 1600's, the disease was seen in England. This particular type of plague was the bubonic plague, which is caused by the bacteria called Yersinia pests. This bacteria lived in rats and other rodents. Human beings were infected through bites from the fleas that lived on these rats. The symptoms associated with plague are bubos, which are painful swellings of the lymph nodes. These typically appear in the armpits, legs, neck, or groin. If left untreated, plague victims die within two to four days. Victims of this disease suffered swelling in the armpit and groin, as well as bleeding in the lungs. Victims also suffered a very high fever, delirium and prostration. During the sixteenth century, plague teased England's countryside with isolated outbreaks. The major outbreaks were in London, due to its large population. Historian Rappel Holinshed wrote: "many men died in many places, but especially in London." At the beginning of the century, London had a few mild winters, allowing the infected rats and fleas (which usually hibernated) to remain active. Contemporary observers estimate that this epidemic took almost 30,000 lives, almost half of London's population at the time. However, church records show this estimate to be exaggerated, putting the actual number closer to 20,000. In 1563, London experienced another outbreak of plague, considered one of the worst incidences of plague ever seen in the city. The bubonic plague took almost 80,000 lives, between one quarter and one third of London's population at that time. Statistics show that 1000 people died weekly in mid August , 1600 per week in September, and 1800 per week in October. Fleeing form the cities and towns was common, especially by wealthy families who had country homes. Queen Elizabeth I was no exception. She took great precaution to protect herself and the court from plague. When plague broke out in London in 1563, Elizabeth moved her court to Windsor Castle. She erected gallows and ordered that anyone coming from London was to be hanged. She also prohibited the import of goods as a measure to prevent the spread of plague to her court. Later, in 1578, when plague broke out once again, Elizabeth took action. This time she ordered physicians to produce cures and preventative medicine. Also, most public assemblies were outlawed. All taverns, plays, and ale-houses were ordered closed. Plague devastated England and its people during the Elizabethan period. Despite all of the hardships involved with plague, there were many advances made. Writers wrote of preventative measures, causes and recommended cures, which led to the basic medical practices and sanitation practices of the time.

|

|

As many writers have stated, the first case of a water-borne disease was probably caused by an infected cave man polluting the water upstream of his neighbors. Entire clans were probably destroyed, or maybe the panicky survivors packed up their gourds and fled from the "evil spirits" inhabiting their camp to some other place. As long as people lived in small groups, isolated from each other, there were not many incidents of widespread disease. But as civilization progressed, people began clustering into cities. They shared communal water, handled unwashed food, stepped in excrement from casual discharge of manure, and used urine for dyes, bleaches, and even treatment of wounds. Several Christians of the 14th and 15th centuries earned status as saints by setting an example of helpful charity toward plague victims. They also were thought to preserve the healthy from the ravages of the plagues. The popularity of St. Roch of Montpelier grew steadily during the 15th century, especially in Italy and Germany. Writers of this time described plague in great detail in their diaries and chronicles. One of the most common observations was the Italian writer Boccaccio's description of people being abandoned in the epidemic. His description was picked up by other writers. Images of abandonment because of plague can be traced from Italy to writers in France and Germany. As cities grew and became crowded, they also became the nesting places of water-borne, insect-borne, and skin-to-skin infectious diseases. Typhus was most common, reported in the 17th century by Thomas Sydenham, England's first great physician. Next came relapsing fever, plague and other pestilential fever, smallpox and dysentery (a generic class of disease that includes what is commonly known as dysentery), as well as cholera. Nonexistent or poor plumbing was merely one of many sanitation factors that gave rise to the Black Death of the Middle Ages. Other scourges are also directly related to human waste. Dysentery is one that has left an indelible mark on history. Characterized by painful diarrhea, dysentery is often called an army's "Fifth column." Dysentary was dentified as the time of the Hippocrates and before. It comes in various forms of infectious disorders and is said to have contributed to the defeat of the Crusaders. Typhus fever is another disease born of bad sanitation. It has come under many headings, including "jail fever" or "ship fever," because it is so common among men in pent-up, putrid surroundings. Transmitted by lice that dwell in human feces, it is a highly contagious disease. Typhoid fever, a slightly different disease, involves a salmonella bacillus that is found in the feces and urine of infected people. Another water-borne disease, cholera, has been one of history's most violent killers. However, through cholera epidemics, the link between sanitation and public health was discovered, which provided the impetus for modern water and sewage systems. Cholera is caused by swallowing water, food or any other material contaminated by the feces of a cholera victim. Casual contact with an infected bathroom, clothing, or bedding might be all that is required. The disease is amazingly rapid-acting. Extreme diarrhea, sharp muscular cramps, vomiting and fever, and then death, can occur within 12-48 hours of infection. In the 19th century cholera became the world's first truly global disease in a series of epidemics. Eventually these epidemics led to a better understanding of the causes of the disease, followed by improvements in sanitation and plumbing. Man has a long history of battling epidemic or plague-like diseases. The treatments have advanced from hoping that a disease will cure itself (most of the time it never did) to administering modern preventive measures, medications and treatments.

|